Understanding Grief from being Locked in the Toilet

This article begins with a skit about coming to terms with being trapped in the loo, then explains how this analogy can help us understand phases we might navigate if we are bereaved.

Feel free to skip the skit using the content page, or to check out my longer article on Theories of Bereavement.

Contents

Skit

Imagine you come over to my house to visit. Perfectly normal occasion, and you have a really nice time. Things feel normal: we chat, play a game, and have some dinner.

Embarrassingly, the need for a poo hits you and, unfazed, I tell you where the toilet is. You’ve not been to this room before and are a bit uncomfortable with it, but needs must and eventually you find the toilet.

Unaware of what’s about to happen, you lock the door behind you and then sit on the loo, spending 5 minutes doing your business. As you’re straining away, you hear a strange noise at the door. You don’t know what it is, but it sounds a bit like a drill. Your trousers are round your ankles. You’re still finishing your business. You’re powerless to be able to investigate. So, for now, you decide you’ll just shout out. Say something.

“Simon, is that is that you? I can hear noise outside”.

The drilling eventually stops, but I don’t reply. You try to put your unease of the drill to the back of your mind. Maybe you imagined it. It doesn’t really make sense. You wipe your behind, wash your hands, and finish up your deed. But the whole way through, your reptilian brain knows something’s off. There’s a threat that you can detect under the surface, nagging away from you. You need to check.

Meaning to have a word with me about this drilling noise, you unlock the door and try and open the handle. Your fingers are still wet, but something’s off. The door feels like it’s locked. futilely. You knock and pull at the door trying to pull it open with pure strength. You doubt yourself. Maybe you didn’t twist the handle right? It doesn’t seem to be working. The door is somehow screwed shut.

“Practical joke”, you think. Uncharacteristic of me. And you shout for help.

“Sigh. I’m stuck in the loo”.

Again, no answer or response.

You keep trying to call me with more aggression and determination as the minutes pass and then think “I’ll phone him”.

Funny; you don’t remember turning your phone off. You turn it on and try to phone my number, but it doesn’t seem to work. “Not registered on network”. There’s something off. You try Wi-Fi to WhatsApp me, but that doesn’t seem to be working either. The phone’s useless.

Maybe you could open the window and call for help or escape, but that too seems somehow locked. You see someone walking by and try and shout out to them,

“Help! Help! Let me out!“

But they, nor any of the other passers-by seem to stop or even notice you there in the bathroom screaming for help.

A good half hour’s gone by. You’re exhausted and sit down to take stock. Picking up your phone, you figure that you will distract yourself and play a game. And there are moments that it works. You’re distracted and almost forget (in playing backgammon) that you’re stuck in the toilet. Then there are other moments where the realization of your predicament hits you and you miss home. You long to be able to leave. There are times where it doesn’t feel real, as though the door will open. It’ll all be a practical joke. Glimmers of powerlessness come over you, alongside other strong feelings. You’re not ready to be in here. you need to get out, but you’re too polite and socialized to try and do anything too drastic. After all, you’re a guest. You can’t smash a window.

As the hours go on without rescue, and it begins to get dark outside, it becomes evident that you’re going to have to sleep in here in a cold dry bath. I say sleep, but you’re restless, thinking of little else but one, your situation, and the discomfort of trying to get a good night’s sleep in the bath. Morning does come and the sleep deprivation adds to the weight of your feelings. Alongside the realization that the world around you is still moving and what will work say now you’re so late.

You need to get out but scanning the room you find a plate of food and water. Who put this here? How did that happen? You’re hungry. You need to eat. But you can’t stop trying to make meaning out of this obsessional almost. What’s happening? Why is this happening? Surely you would have heard the door open with that rough night’s sleep you had. Yet no meaning comes or answers to why or how you’re in the toilet.

Later in the day, social convention goes and you put all your effort and anger into breaking free. Trying to smash a window, cause a mess, break down the door, but acting on anger is worthless. You’re still stuck. And worse still, you’re damaged by it. Hand bleeding, cold breeze blowing through the smashed window that you couldn’t fit out of. It doesn’t make sense. You’ve tried everything to escape. Nothing seems to be working.

There’s a shimmer of acceptance as you pick up a book in the room [‘how to poo at work’] and read, not to distract yourself, but more out of boredom to pass the time. You realize though that it’s not acceptance. It’s hopelessness at being trapped. And you feel the heavy weight of depression.

As days go by, food keeps coming. No meaning is given. You begin to oscillate between trying to escape, but also accepting your situation, making the most of it, treating yourself to a nice bath or a shave. And in stopping fighting escaping, you begin to accept it and even to take interest in the books you find or adapting the place to better meet your needs, like using the shower curtain as a duvet.

You’re no longer fighting to escape the toilet. And in stopping fighting, you realize that you’re ready to leave. That it was You keeping yourself here the whole time, blocking the door with your own foot. You mourn leaving, just as you mourned when you realized you were trapped in the toilet. But this room will always be part of your house, a room that you can return to with doors unlocked.

Trapped in the Toilet: Explaining grief

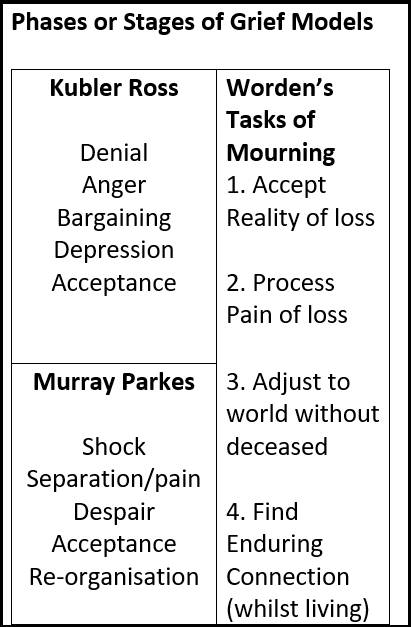

There are lots of different theories of bereavement. I want to give a disclaimer that there is no right way to grieve a loss or a change. There’s no single theory of bereavement that is correct. This analogy of coming to terms with being trapped in the toilet lends itself more to stage-based models, like Kubler-Ross, but the bereaved don’t necessarily journey in a linear way through set stages – we oscillate, relapse, sway.

I’ll analyse the skit though and explain 14 different stages (or scenes) that mirror grief

1. Unexpectedness

The loss hasn’t happened and most of us wear an existential armour that blocks us from the reality of death, and certainly that affecting us or those close to us. We know everyone dies, but it isn’t within our awareness that death will affect us. Stage 1 is pre-bereavement. Our life is occupied by other things. It’s the rocking up at the house, playing a board game, having a meal, having a nice chat. the opposite of being locked in the toilet.

2. Shock

The second stage is shock, in the skit it’s where the screws are going in the door and you’re aware of something being wrong but you’re mid-poo and unable to engage in it. You’re shocked and there’s an angst as that existential armour of unexpectedness is suddenly falling off. The self is in a combination of denying the information, distraction from it, and an overwhelm from its potential that numbs us to an absence of feeling.

3. Distraction

In the skit, this is wiping your bum, washing your hands, and finishing the poo: finishing your business before you can check or even entertain the possibility of a death. People who have a loss, particularly a bereavement, are often incredibly distracted early on. There’s lots of practicalities to sort out like the funeral, notifying people, & taking on roles that the person had. These are practical things that get in the way of even checking or knowing a death has happened, and it’s why many people won’t even realise they want to process a loss in counselling until weeks after the funeral.

4. Realising you are trapped

The pulling at the door and then realizing that you’re trapped. It’s an attempt to deny it, an immediate resistance to the acceptance that somebody has died, that a loss has happened. It’s encountering it and having space to quite painfully and suddenly encounter the fact that we are trapped in the toilet.

5. Bargaining

In the skit it’s shouting out to people outside, trying to phone someone or connect to the Wi-Fi, screaming for somebody in the house. It’s trying to be noticed and to resist the reality of the loss, the death, whatever we are grieving. Bargaining is an attempt to stop or change the circumstances.

6. Distraction

In the skit, it’s a momentary pause to play backgammon on the phone. Grief and the feelings and alterations to the Self are immense. This scene could easily go between every scene. If we just embraced the wave of feelings and existential angst of grief without pause, the Self would be obliterated, so distraction from grief is a very normal tool to manage its pressure. There are models of grief that actually highlight that oscillation between painful griefworks and life outside that may feel a distraction from that griefwork. Distraction isn’t worthless, it is part of the process rather than actively avoiding it, distraction is pacing ourselves.

7. Acceptance by force

This was going to sleep when it got dark, not because I wanted to sleep in the skit, but because the night forced me to. You start to feel tired, and physiological needs like thirst and hunger might come over you. You’re not choosing it. you’re adapting to the reality of the grief, which means practically doing things even if we haven’t accepted it.

8. Giving up Resisting

In the skit, going to sleep represents this, just as with eating the meal or eating the water that’s left there rather than assuming that it’s poison and pushing against it. It’s again an oscillation, not quite accepting, but channelling our energy elsewhere. It’s a sense of coming to terms with it mostly out of exhaustion rather than purely resistance.

9. Missing the past

Missing life outside of a toilet. It was realizing all those responsibilities that are gone or shifted: work, relationships, people outside of that room. It’s grief work. It’s missing what isn’t there. It’s in terms of bereavement. It’s around missing the person. Less fighting against it and more just wondering how those things will be without them. In bereavement, connecting with the person and missing them is a much bigger part, as with missing the life you had before – however in this skit it was harder to represent.

10. Meaning Making

Again, trying to make meaning of a loss is much bigger than in this skit. It can include spiritualism – trying to come to terms with magical things in the skit (window not smashing, plate of food appearing), and there can be a sense of bargaining with that as well trying to connect spiritually with the person who’s died. Praying, making amends. Trying to make sense of what has happened, trying to have a purpose out of it. How do we conceptualise the death in terms of our faith, philosophy, meaning, and purpose.

11. Anger and acting on it

It’s hard to represent the strength of the anger than can be evoked from a death. In this scene, I let go of social conventions to smash the window in an attempt to escape, however it doesn’t work. I was thinking about how people who are trapped in cycles of grief may well do things that are very active in feelings. Anger can be a wonderful emotion because it drives us forward. It doesn’t help us to give up. It gives us that kind of last ditched effort to escape. But I also wanted to emphasize that sometimes acting on our anger can also harm us. If we smash the window, we might bloody our hand or make the room colder with the wind. In anger, we might fall into addiction. We may try and harm ourselves. We may make reckless decisions and all of that can be motivated out of a desperation to try and stop the grief and the situation we found ourselves in locked in the toilet. Anger is a natural stage of grief.

12. Hopelessness

It can feel a little bit like acceptance. At least it’s accepting that there’s nothing that we can do to change a situation. But that hopeless scene is where more stronger feelings of depression, sadness, numbness, loneliness, the real stuck feelings, start to arise and those feelings are very natural and adaptive to being stuck in the toilet. We are literally trapped and it’s okay to feel trapped, to feel depressed. It’s part of coming to terms of it. Those feelings that are less active and aren’t driving us, but it’s adaptive because that is the situation. You’re stuck in the loop, and it is something to feel hopeless darkness in. You are mourning.

13. Acceptance

Rather than putting energy into trying to escape, or feeling utterly beaten, downtrodden, and depressed by the result of being locked in the toilet; acceptance is where I started to do things like use the bath, shave, read all of the books, reorganize things, turn the toilet paper tubes into a pillow.

It’s being able to have accepted what has happened and adjusting life accordingly without trying to fight it, without trying to change it, almost trying to make the most of it.

14. Reintegration

Realizing that we are in the toilet, but we can let ourselves out of it. realizing that our grief is one of the rooms in the house and that room is never going to change. It’s never going to get less intense. We’ll always need to visit it. That’s one more thing about the toilet: we do have to visit the loo a few times a day. We stop feeling trapped by the grief.

It might be that rather than traumatic memories of the death (locked in the bog), and the painful feelings from this, instead there are happy memories of the deceased and your time with them. You feel you can and are connecting with them, and that connection doesn’t block you from connecting with life. Having other rooms in the house but also being able to revisit our grief. It’s a myth that we ever get over a loss. How can we ever get over the loss of our attachment figures and the people who are important to us? They will always be important to us, but we won’t be choked up as much or as often.

End

If you look at this image, you’ll notice a lot of the stage-based models of bereavement reflect some of the scenes and my explanations from this skit.

I like speaking about grief as people can blame themselves, feeling they are stuck in patterns of wrong grief that is their fault when grief is a normal process that they aren’t doing wrong.

Grief isn’t a mental health issue either, it’s a natural process, coming to terms with losing our attachment figures. It’s normal to have these intense pangs, that urge to escape, mystical thinking, moving against social conventions, leaving the rest of the household to be trapped in the loo. It’s a recognized process.

Feel free to read my other article for much more on theory, and I hope this analogy has given you acceptance and new understanding of the process that you or others might go through when they are grieving.

Simon is a Person-Centred Counsellor in Oxford working remotely and in person. He has lived in the county his whole life, and the city for almost 20 years. He appreciates the beauty of the city, nature, and connecting with people to help bring about meaningful change.

He is also a geek – who gets tremendous joy from gaming, crafting, cosplay, and creativity