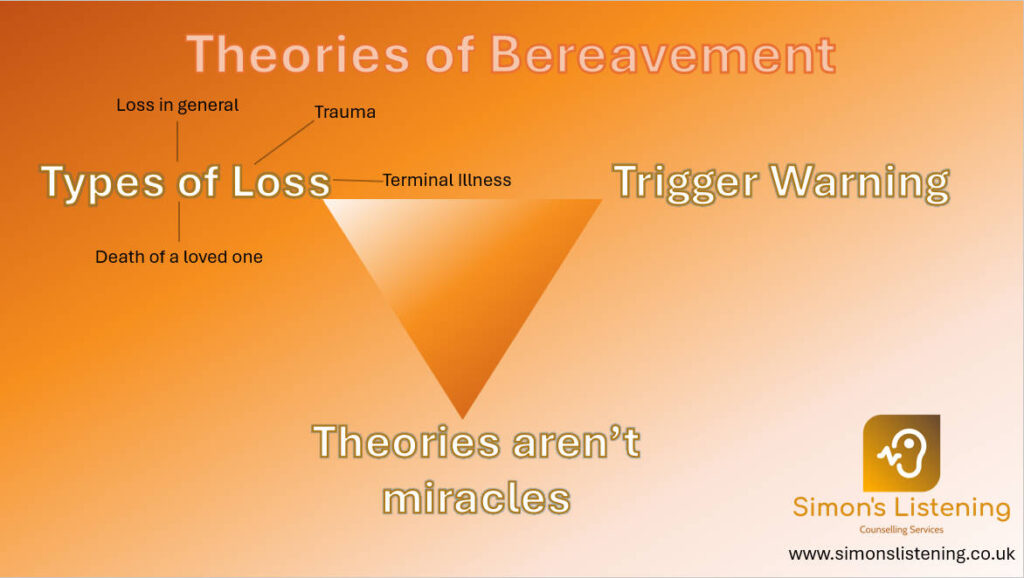

Theories of Bereavement

Introduction & disclaimers

This article is on Theories of Bereavement and how theories can help for different people at different stages of their grief.

Bereavement is the death of another that we have personally been affected by (be that family, a friend, celebrity, or even someone we cannot speak to others about).

Some theories also affect our own death: either from death anxiety at our mortality or in a terminal illness.

It can also be applied to Loss in General of many varieties.

Trauma often coincides around deaths and can complicate the grief, but is slightly outside the scope of this article.

If this article becomes triggering, do give yourself space to look after yourself

Overview

This article will cover the Reasons for theories, Symptoms of Grief, then the bulk of it will cover the Theories themselves.

At the end I will give some tips to grieving. If you are looking for solutions or grieving yourself, feel free to click this button to skip to that section

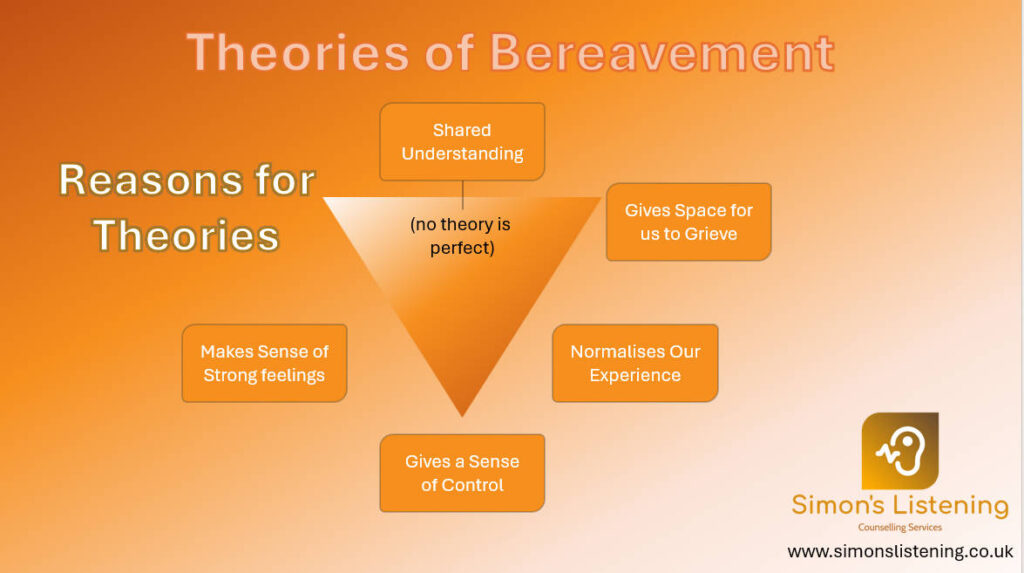

Reasons for Theories

- Theories make sense of strong unexpected feelings (like anger or dissociation)

- They gave a sense of control when we feel out of control

- They normalised unexpected experiences which takes away that sense of isolation, and provided a reassurance that is it a normal part of the grieving process

- Theories can stop us doubting ourselves (if we are somehow grieving wrong), and that self-doubting can actually block us from being able to grieve, so in that sense – it gives us space to grieve.

- Theories provide a shared understanding of the grieving process which can help us to work therapeutically with grief, and prepare us for being with clients in the midst of theirs.

No theory is perfect. They resonate with different people at different stages of theri grief

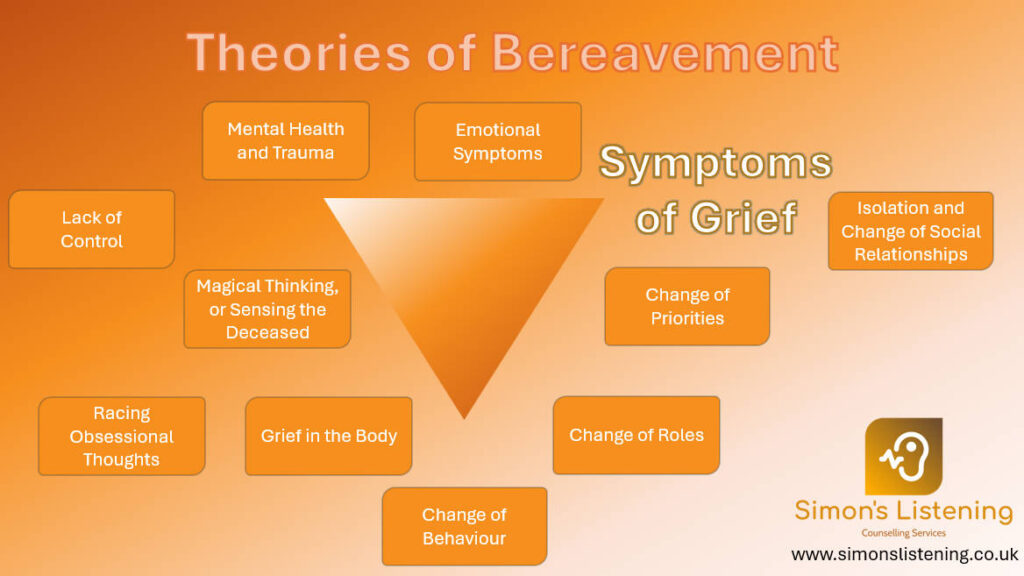

Symptoms of grief

- Emotional Symptoms:

Dissociation or Numbness, Anger or outright rage, Panic Attacks, deep existential dread, Death Anxiety, pangs of grief with intense depression or volatile sobbing. - Mental Health and trauma:

Relapsing into old patterns of difficult mental health, and visceral trauma responses from physically experiencing the death or decline of a loved one - Lack of Control:

The feelings are strange and bubble up, beyond out control with a sense of powerlessness - Magical Thinking, or Sensing the Deceased:

Seeing, hearing, or in other ways sensing the deceased – yet know they can’t be there. A fear of going mad, yet their phantom keeps appearing. We might be trying to make deals with gods or practicing magical thinking to only bring them back. We may have created a shrine to the person and be in two minds if this is okay, and what to do with their belongings or photos. - Racing Obsessional Thoughts:

Our brains may feel hijacked with incessant thinking about them, which can trigger those intense feelings. - Grief in the Body:

Maybe we are experiencing similar symptoms in the body to the person who died and are overcome with a fear of meeting a similar fate – and in fact bereaved people are more likely to have physical ailments post-bereavement. We may also find bodily changes with things such as our sleep or eating patterns. So rocked by grief, we may struggle with those things that physiologically came so easily before in our routine. - Changes in Behaviour:

Acting in ways we didn’t expect, such as unexpected outbursts. We may feel as though our personality is crumbling, and unsure of this person we are becoming. - Changes in Roles or Identity:

We may have had care responsibilities for the deceased and now experience relief from that. We may have more free time, but do not know how to use it; and it being accompanied by a sense of meaninglessness or purposelessness.Without the deceased, our familial role can also shift – we were their child, partner, lover, friend, parent….and now our identity is shifting, and the tasks the deceased did can fall on us. We might be inundated with (not just the tasks the deceased would do), but tasks around organising the funeral or other arrangements that can really feel quite overwhelming, and our resilience or capacity is severely diminished. - Change of Priorities:

Work, relationships, competitiveness, hobbies… they can lose significance. There can be a lostness and annoyance around the pettiness and squabbles that before peaked our interests, or the world cares so much about. - Isolation and Social Relationship Changes:

We can also be stigmatised for grieving: There are no magical words to make someone feel better, and so out of awkwardness people can avoid us. Furthermore, the death-denying nature of our culture can add to that sense of isolation, or it becomes this taboo subject where people don’t want to talk about your loved one after the funeral – when a significant attachment will always have importance to you, especially at anniversaries. All of this together adds to the loneliness and isolation of bereavement, which can permanently shift our identity within society and our relationships. Not to mention the toll that grieving itself can weigh on the social batteries, where introverts may increasingly need to isolate, or extroverts need more connection in the face of a world that’s closing in.

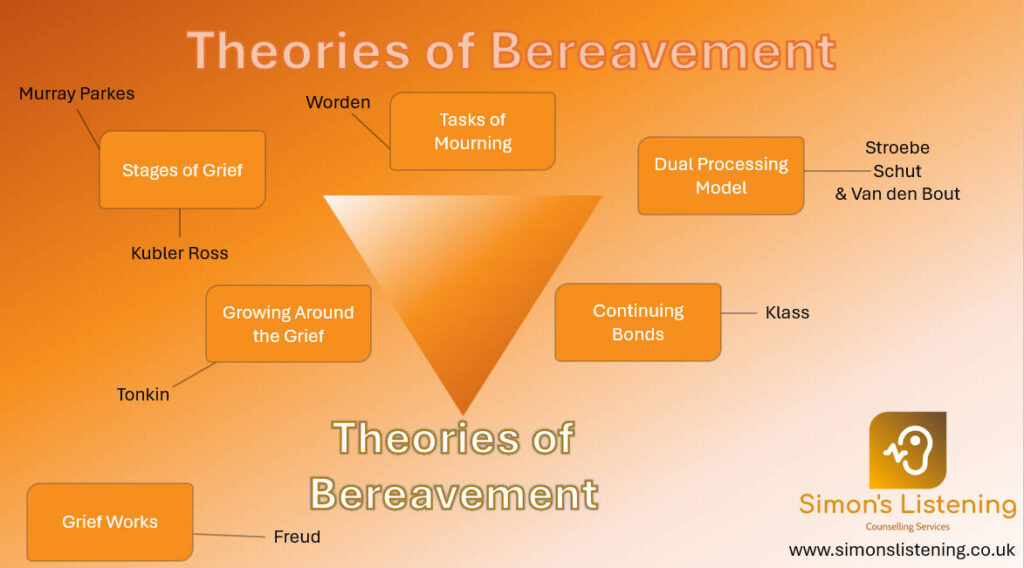

Theories of bereavement

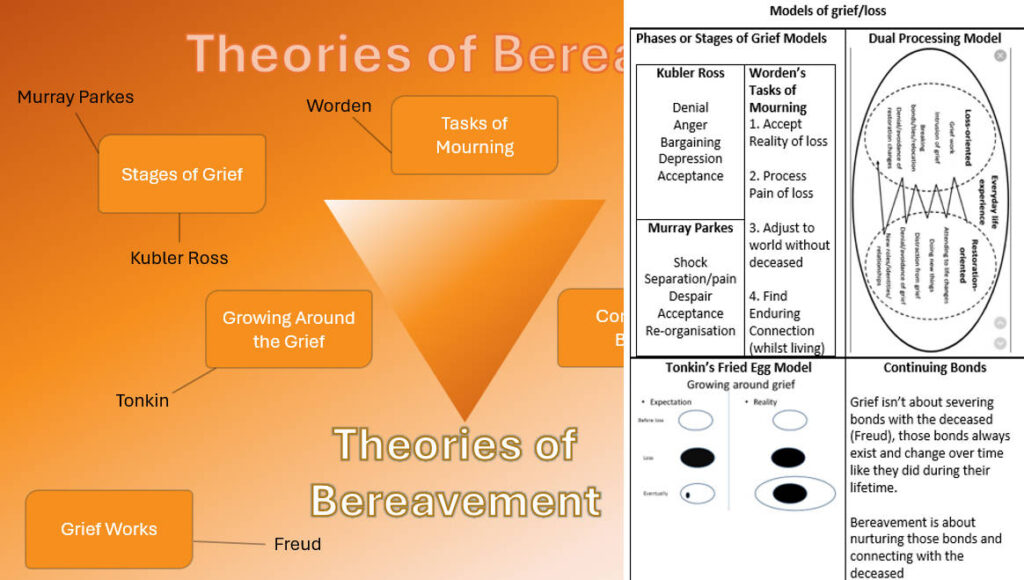

These are the six models we will cover. Three are stage or task based, then we’ll look at the Dual Processing Model and finally Continuing Bonds and Growing Around the Grief. The black represents the authors of the theories but there have been many contributors to each.

Sigmund Freud

I’ve included Freud in there just for reference. His idea of Grief Works was that we need to sever our link to the deceased and release the energy we have attached to them, resulting in this great cathartic pain, whereas avoiding this can result in a depressive episode called melancholia.

It was The early theory of grief, and the link around painful grief and an attachment figure are helpful, but it propagates ideas like “moving on”, “getting over it”, or “detachment” from the deceased that more modern theories don’t hold.

Stage or Task-based models

The first thing to mention with these three Stage or Task based models, is that it doesn’t have to be rigid or sequential. A person may pass from one stage to another in any order, may skip stages, and may move back between them at different moments as they process their grief in different environments.

There also isn’t a ‘time limit’ or expectation to be at a certain stage, nor should we be forcing a person (or ourselves) to be in a Stage we’re not. Rather see it as a flow that tends to move in that direction but is really a very individual process.

Dr Elizabeth Kubler-Ross

Probably the most famous theory of grief, but it’s actually a theory for someone diagnosed with a terminal illness, rather than for bereaved people, which is partly why acceptance is the last stage.

It’s quite an emotion focussed model, and can be helpful to explain strong feelings and assist our acceptance of them.

- Denial:

There may be a numbness or dissociation and depersonalisation here. A refusal to believe the medical evidence that the person has died (or that we are going to die), Trying to carry on as though life is normal. The Existential Angst is massive to process. Separating ourselves from the enormity of it through denial is protective from being completely overwhelmed. This is also a stage we may find ourselves returning to, questioning if it is real then being hit by the reality of the situation. - Anger:

Anger is a powerful motivating emotion that forces action – it fires us up to prepare us. The approaching death of ourselves or of people who are significant to us, can create a righteous anger of how unfair it is, and drive us to try and do something about it, or rage at an unjust world. It may also not be anger but a different strong active motivating emotion like jealousy, anxiety, dread, fear, or a deep irritable sensitivity.

The magnitude of that anger can feel unfamiliar or even scary. With men, for example, anger can be demonised as violent or dangerous. Anger around bereavement can feel disconnected to the reality of our situation, which can make it particularly difficult to accept or express. Anger that is difficult to express can end up being displaced onto seemingly irrelevant things.

A bereaved person may find themselves triggered by things that wouldn’t before bother them like queues, or petty disagreements with the family. The enormity of anger due to their terminal illness, or the grief of losing a loved one is too big to process, and it can trickle out – displaced into little moments that are hard to accept and we can beat ourselves up over. Theories, like Kubler Ross’s, can help us to explain outbursts and stop the guilt we might feel if we find ourselves becoming angry. - Bargaining:

With a terminal illness this may look like finding alternative remedies, prayer and bargaining with God as we understand them, or more magical thinking such as “if I do this good thing, then I will be healed”, “if I follow this ritual, it will be okay”, or a sense of guilt such as “I deserve to have cancer because I did this horrible thing, and if I make amends it will go”.

In terms of bereavement: bargaining can reflect the prayer, magical thinking, or striving to end the pain of the separation; a longing to ‘get over it’. It may also involve trying to create changes in our life: the new job, relationship, activity, or investing our emotional energy outside of our grief – acknowledging the magnitude of our grief, desperately trying to push it away by seeing if something else can fill that hole.

Bargaining can give a sense of hope after acknowledging the loss, and realising our strong feelings aren’t bringing the person back. In and of itself, it’s a more active form of denial, and helps us know we have tried everything that is humanly and spiritually possible to ‘deal’ with our grief. - Depression:

The hope of surviving, or the return of our loved one is gone. There is a hopelessness, and sense of giving up. Meaninglessness and Purposelessness can ensue with: deep existential dread, pangs of grief, despair, and insatiable tears.

Depressive feelings are less active than the feelings within the Anger Stage and it can be incredibly isolating and lonely when a striving to escape our grief no longer works.

Depression in the face of these huge existential issues of loss also feels apt, it’s too big and a sense of powerlessness to it is overwhelming. Depression here is also a stage of grief – it’s not clinical depression, and hearing that can be reassuring for people who have gone through clinical depression and fear a relapse. - Acceptance

This stage makes more sense if we are dying compared to if we are bereaved. Terminal patients may report a sense of peace or completeness, a readiness to die and accept what is happening to them. There is no more fighting, but their death isn’t overwhelming. Instead, they are ready.

In terms of bereavement, acceptance means the overwhelming feelings are triggered far less often and feel much more in control. The memory of the deceased is likely more balanced. There could be a reintegration back into society and less existential questioning of it. Maybe even that sense of peace.

Because Kubler-Ross is more of a terminal illness model though, Acceptance doesn’t reflect the experience of bereaved people – rather than a sense of ‘moving on’, I find other models give better example later stages of the journey of bereavement.

Colin Murray Parks

I recommend his book called Bereavement. It was very helpful for me in writing and researching this article. He was also the Life President of Cruse Bereavement Care which is where I first encountered many of these theories as a bereavement volunteer offering counselling to bereaved people.

Parks similarly has a model with similar stages to Kubler-Ross’s Theory

- Shock:

A disconnection or numbness, both in our feelings but also in our actions… a “going through the motions” stage. This shock and disconnect can be especially helpful when there’s so much stuff to organise in that first month. It prepares us to survive and process the magnitude of our loss. The shock/denial/numbness can also sometimes be underestimated. This contributes to this strange cultural belief that we should be fine after the funeral, when in reality we are often just leaving that shock stage. - Separation and Pain:

Not so much denying the death as it is pining for the deceased and trying to locate them. Processing the reality of the separation; that they can’t be located, replaced, or the void they have left behind be filled. This is accompanied by deep emotional and psychological pain as that void’s reality continues to be realised in different areas of life. - Despair:

Characterized by much less active emotions than in the Pain Stage. The reality that the person has died and cannot be replaced instead leads to despondency. Depressive empty feelings, purposelessness, meaninglessness, and withdrawal often accompany this Despair –metaphors like being lost, alone, afraid, in a dark abyss encapsulate it. - Acceptance:

The intensity of the strong feelings or pangs of grief in previous stages diminishing and feel much more within our control. Acceptance doesn’t mean ‘getting over it’ – but does mean being more at peace with it. - Re-organisation:

Less intensity of feelings, and a return to a sense of ‘normality’ or ‘realness’. An internal reorganisation within the Self that has been knocked by the reality of the death, and no longer feels so foreign. An external re-organisation back into society; regaining relationships, purpose, joy, meaning. The bereavement may continue to bring distress, but generally at this stage, the person’s world has adapted to the reality of the loss without that jarring them.

Worden’s Tasks of Grief

Here there are four tasks which the model suggests must be actively worked through during the grieving process. It somewhat mirrors Kubler-Ross or Murray Park’s models, as well as linking on to other models we’ll cover later like Continuing Bonds.

Little disclaimer here, that we need to feel safety and containment to process strong emotions. They are called Tasks that must be actively done, but I don’t want us to risk traumatising ourselves by viewing them as task we must do before we are ready to – it takes time to reach each stage and navigate it.

- Accept The Reality of the Loss:

Moving away from denial, shock, bargaining, etc (that might protect us from the loss), and recognising that the person has died. It’s a logical acceptance, but also an emotional one, and that reality keeps hitting in different areas of life as we realise the space left in the absence of the deceased. They have died, and they continue to die as we realise what their death means. - Process the Pain of the Loss:

Involving all those strong, previously mentioned, active emotions or despondent emotions. An overwhelming pain that feels unmanageable and incontrollable. - Adjust to a world Without the Deceased:

Adjusting to changes in:

– the roles they had within the family

– the tasks they performed that we’re left with

– being in environments that we have memories of them with, but they are no longer there

– the loss of them and what their connection provided for us, the intimacy of that.

– a change in our identity in the face of the loss

– building new social structures without them

– returning to the world and culture when our world has been existentially shook. This may, for example, mean our returning to work or other commitments.

Adjusting can feel like relearning how to walk. In many ways, adjusting is returning to a known world, yet doing so without the decease can feel alien, foreign…disturbing. - Finding an Enduring Connection with the Deceased:

balanced with the previous task of adjusting in the world without them. This stage is about keeping the connection alive with them and accessible in a way that is meaningful – without being overwhelming or taken away from the world: Embodying them, remembering them, finding meaning from your relationship with them.

Maybe you hear a song on the radio, and that connection is reignited with them; or visit the grave on an anniversary to spend time with them.

The Dual Processing Model

Stroebe, Schut & Van den Bout's 'Dual Processing Model'

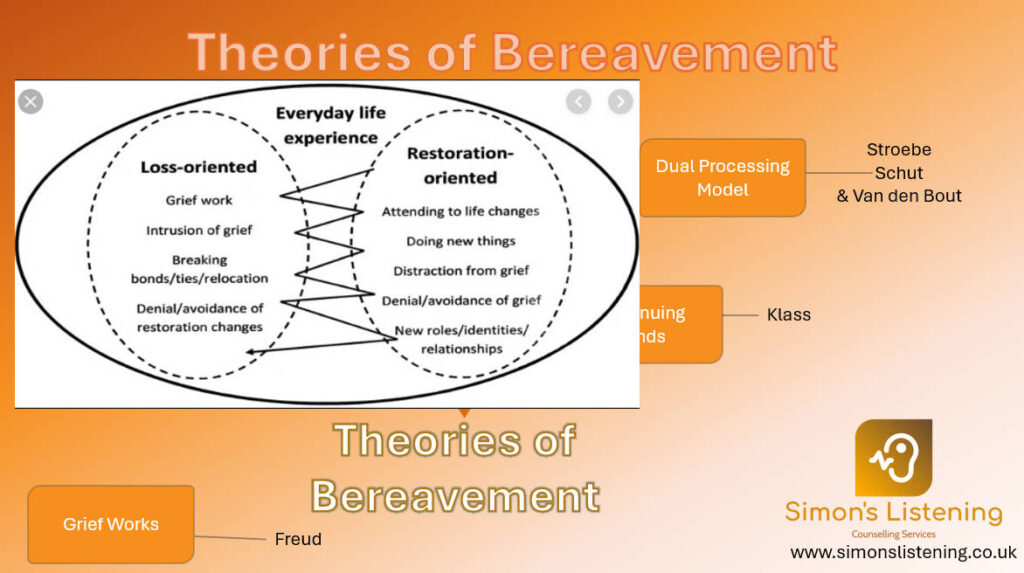

Rather than moving through discrete phrases, the Dual Processing Model talks about Oscillating, or bouncing between different Orientations or states.

Bereavement is huge. Grieving is like being forced to take on a new identity. If we were to complete the grieving process instantly, the Self would be annihilated. Often Defence Mechanisms like Repression are almost seen as defective, but it’s the body’s way of protecting itself from overwhelm, and without it we would be traumatised. This is what this the Oscillations between those Orientations do – it helps bereaved people to cope.

Many bereaved people will describe their grief like waves – there are these intense pangs of grief. They then fade, and there may be an energy or sense of normality, ‘til those waves hit again.

The Dual Processing Model reflects this. It sees the process of grieving as a normal oscillation between a Loss and a Restoration Orientation. Orientations happen in waves, and rather than completing one or the other you oscillate between them like a pendulum.

The Loss Orientation is the painful stuff that we typically think of when we think grief.

Grief Works

The painful realising that the person has died

Intrusions of Grief

(the overwhelming feelings that catch us off guard)

Breaking Bonds/ties/relocation

The changes in identity, loss of roles, processing what their relationship means to you – a ‘letting go’.

Denial/ Avoidance of Restoration Changes

Interestingly, this element of loss is not wanting to be in the other orientation, but wanting to stay in the grief as it connects us to the deceased which doesn’t feel compatible with restoration

The Restoration Orientation is what people talk about when they picture ‘moving on’. This Restoration, this adapting and reintegrating, is essential. It’s part of the grieving process and it happens alongside the Loss Orientation.

Attending to life changes

Doing new things

Or maybe even doing old things that feel new without the deceased

Distraction from grief

Giving ourselves permission to be distracted from it, accepting this as part of grieving

Denial or avoidance of grief

in much the same way as the Loss Orientation had a desire to not be in Restoration, it’s natural to not want to be in the agony of Loss

New roles/identities/relationships

And permission for these new things to form without it undermining the significance of the deceased

Both the Loss and the Restoration are necessary parts of the grieving process.

> Getting stuck too heavily into the Restoration can mean we repress the pangs of grief, and it bubbles out in more painful maladaptive ways.

> Getting stuck too heavily into the Loss can mean we are distanced from the world, and cannot connect back with it.

Something I really like about the Dual Processing Model, is the permission it gives to flow rather than a ‘right way to grieve’. It can also give us a sense of Acceptance that we are not bad – nor have we forgotten the deceased, if we start those Restoration changes.

I finally like how it explains the confusion or imbalance a person may feel, like there are different conflicting parts of themselves

Acknowledging we are in one Orientation at this moment and that’s okay, ‘it’ll pass’, and we can move back to the other.

Continuing Bonds and Fried eggs

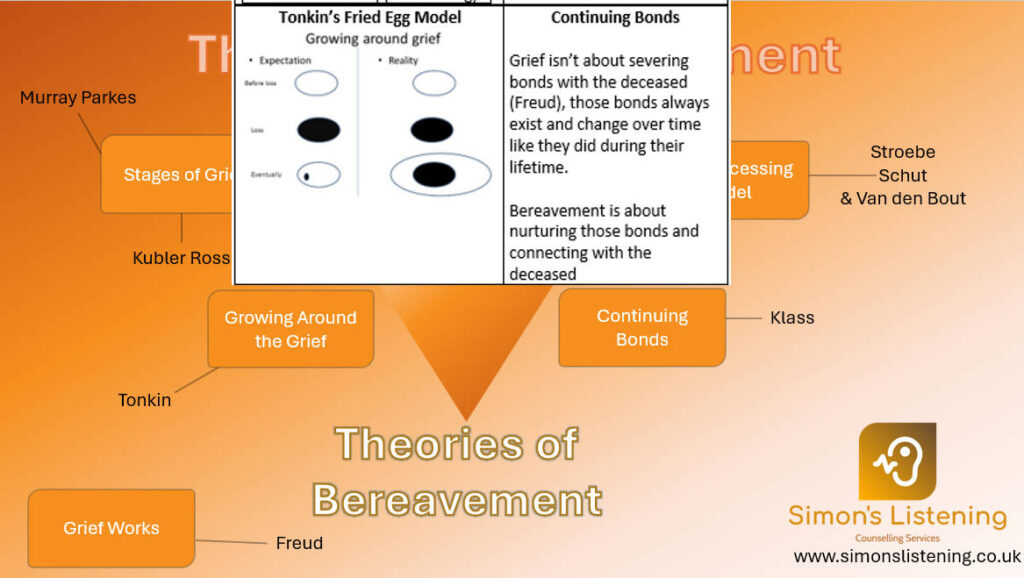

Dr Tonkin’s Growing Around the Grief (or the fried egg model)

Imagine that you crack an egg into a cold frying pan. All you can see is the yolk, because the white is transparent. You turn on the stove and as the oil heats, that transparent outer part of the egg gradually turns white until you see it. The yolk seemed like it was the whole egg, and now it is only a fraction of it.

Dr Tonkin is a counsellor, and she writes about the expectation that grief is this thing that is huge and all-consuming to begin with but will gradually fade and get smaller as we process and the years go on.

Instead, her experience from her client-work was that the grief never gets smaller – just like the yolk doesn’t in a fried egg. Instead, as the heat of grief comes, the person’s life grows and expands but the grief is always there.

There is no ‘getting over it’. We don’t “Move on”, or “stop grieving” – how could we ever forget our significant attachment figures? Instead, life grows around the grief. I’ve spoken to numerous bereaved people who have said things like “I’m scared to move on” or “if I stop crying, I’m afraid I’ll forget him”.

Growing Around the Grief gives a message of hope, that we don’t have to move-on or forget them – they’ll always be significant to us. We don’t have to be afraid of them truly disappearing, just as our grief at their loss never goes, life grows instead.

This is also my experience of people who have had bereavements – even decades ago. Dates such as birthdays, death days, and Christmas likely always hold significance. There are still times those pangs of grief will hit us with a good cry, but over time it’s less overwhelming.

Imagine you threw a bouncy ball horizontally in a metal box. It would hit the walls dozens of times as it kept bouncing about, and that’s like our grief intruding on us.

Over time, the bouncy ball is the same, but instead of a box, it’s a room – the pangs of grief still knocking us as the ball hits the walls, but it collides less often

If you have recently been bereaved and feel overwhelmed or lost with strong confusing feelings, this model can be intimidating – like you’ll be this way forever. At different stages of your grief journey it can be comforting to know you can connect with your loved one

Continuing Bonds (Klass)

When a person dies, the expectation is that they cease to be, and we lose our connection and relationship with them – which is why we grieve; this was Sigmund Freud’s idea of painfully severing the attachment to the deceased.

Continuing Bonds radically challenge this notion. Instead, our relationship with the deceased continues and changes even after they have died. They are dead, but they haven’t ceased in us – the relationship continues evolving.

There’s a lot to be said about continuing bonds and the relationship with the deceased:

How can we work to build those bonds in an enduring and healthy way that acknowledges the grief and enables us to live in the world they have left behind?

Some aspects of continuing bonds include:

- Processing emotional difficulties that we are left with, or unresolved situations between us and the deceased.

- Being less overwhelmed by the painful sides of grief, or of traumatic information surrounding the death.

- Reaching an objective overview of their life which changes over time as we relate differently to them and find out more about them.

- How they continue to live (in the sense that you still relate to them and connect with them).

- It is forgiving the person for leaving you.

- Sorting through belongings, photos, and their life story in a way that characterises their life for you as the individual – recognising others will have a different relationship with the deceased and experience them differently to you.

- Creating a place to connect with them – a memory box, a shrine, or visiting a place such as the grave or other significant area for you/them.

- Being able to connect with them as you understand it, which may even have a spiritual dimension to it.

- Talking about the deceased or sharing memories of them.

- Meaning making of their life (which is a whole theory in and of itself).

- Embodying messages from them and recognising how their life and imprint are alive within you.

- Reviewing your relationship with the deceased and reflecting nostalgically on the journey both before and after they have died.

- Passing this memory and relationship with them on to the next generation, so keeping a sense of them alive.

As a counsellor, I spend a fair bit of time talking with people about death or the fear of it, and with that, I often reflect on my mortality, or of the people I love most in life – like my wife or my sister – and if they might die.

I don’t know how I’d grieve for them, but I have a plan and it might sound a bit morbid. It’ll be painful, but a beautiful way to connect with them and build continuing bonds, whilst realising their absence and the intensity of feelings associated with that:

After they’re cremated, I’d like to eat thirty kinder eggs. I’d then like to put their ashes inside those orange capsules and take them to thirty places that were significant to them – significant to us. It’d be a way to mourn, to connect with them, and also realise the pain of their absence in those thirty special places

So that was continuing bonds – finding an enduring connection with our loved ones.

Top Tips for Grief

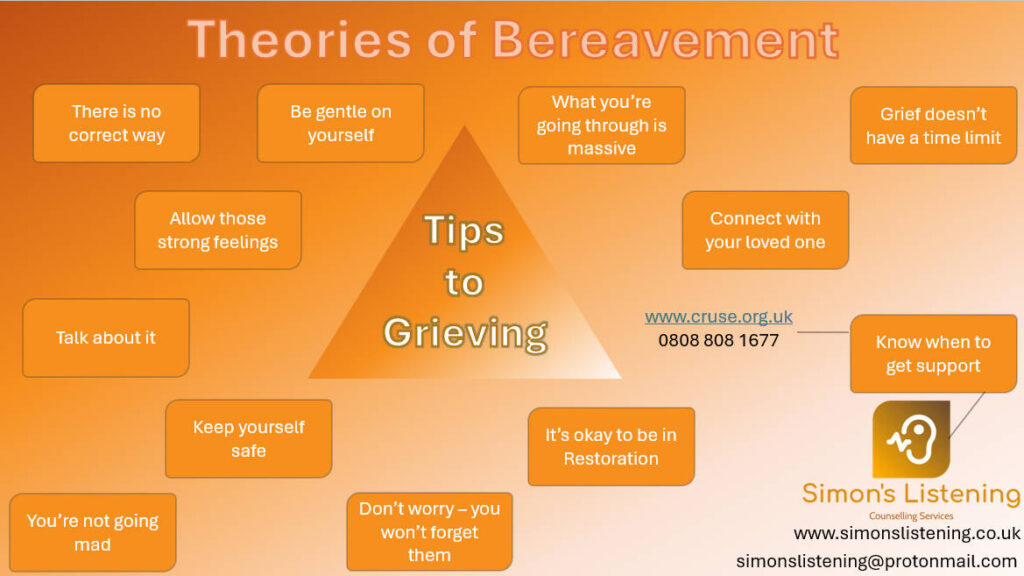

Tips for Grieving

1. There is no correct way to grieve

Everyone is unique, so however you’re grieving is fine. Models can often fall short, and be biased by cultures, genders, or being neurotypical; so, treat it like pick and mix – take what’s helpful for you.

2. Be gentle on yourself

Death is one of the hardest human experiences you can go through. Try to give yourself compassion – it’s normal to feel the intensity.

3. Allow those strong feelings

It likely feels uncontainable or overwhelming, but letting go and expressing yourself can bring relief.

4. Talk about it – even years later

Share memories with family and close supportive friends or others who knew the deceased.

5. Keep yourself safe

Protect yourself from being retraumatised. Death is the ultimate expression of a loss of control. Do what you need to keep yourself safe. That may mean evaluating your priorities, and choosing who is safe to express yourself around.

6. You’re not going mad

These feelings may feel strange and intense, you may feel numb or dissociative, you might see or talk to the deceased and wonder if you are hallucinating, you keep trying to make deals to bring them back knowing it’s impossible, your sense of self may be going, it might feel like you have to reinvent yourself, and joy may have vanished from joyful things. All of this is common, you are not going mad.

7. Don’t worry, you won’t forget them

Even if you stop crying or being in that dark hole, they’re a part of you, and their significance won’t vanish.

8. It’s okay to be in restoration

Making new friends and relationships, having fun, organising your life, having transitions, or a change of circumstances like moving. Those elements can often feel disrespectful to the deceased, but they aren’t – living your life is a part of grieving.

9. What you’re going through is massive

The biggest existential crisis is around death and endings, and you are mourning a loss. Acknowledge that, you’re not weak or defective for being so knocked by it.

10. Connect with your loved one

Just because they are dead, doesn’t mean your relationship has stopped. They’re alive in and through you, you will keep processing and relating to them over time. It’s okay to find time to connect with them.

11. Know when to get support

For emotional or even practical support. That may be with friends or family.

It may also be with organisations such as Cruse Bereavement Care. They have a wealth of resources as well as providing short-term bereavement support, support groups, meetings for people bereaved by suicide, and social groups for others who have also been bereaved.

You can also consider counselling.

There are a wealth of experienced bereavement counsellors out there, and you can contact me. I’d love to journey with you, even in the painful stuff or within the magic of continuing bonds where the person comes alive as we talk about them.

You can also follow me on YouTube or on Facebook.

You may also want to check out this article on Death Anxiety

Simon is a Person-Centred Counsellor in Oxford working remotely and in person. He trained and worked with Cruse Bereavement Care in both their committee and seeing clients for bereavement support and continues offering a safe place to grieve as a counsellor